As organizations adopt AI, there is expected to be a proliferation of AI agents that may well outnumber the number of employees in a company. Just as humans need to be authenticated and authorized to access applications and data, AI Agents will require similar capabilities. In this article, we will explore some of the most fundamental concepts of Microsoft Entra Agent ID, while keeping in mind that this domain is rapidly evolving and that Entra Agent ID is in public preview at the time of writing, and that Microsoft may change its design or implementation.

I have already written about AI agents in the enterprise and the three agentic AI access patterns. You should first read that article since Entra Agent ID is conceptually based on the three agentic AI access patterns described in the article.

The following sections outline the most important characteristics of Microsoft’s Entra Agent ID platform and shed light on their vision and strategy for agentic AI in the workforce.

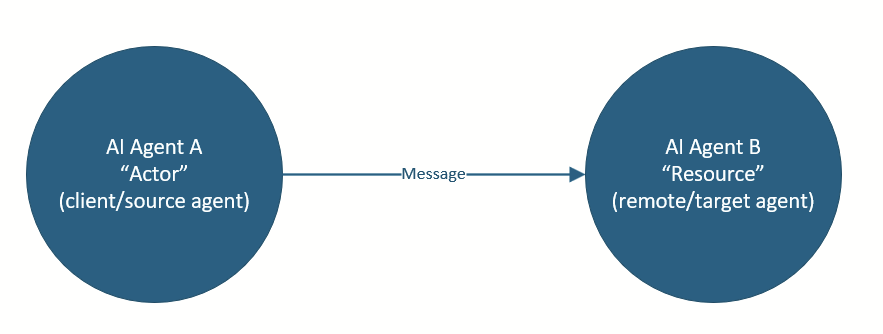

AI Agents as Actors and Resources

AI agents can be actors as well as resources, which means that AI agents can communicate with other AI agents, even in complex multi-agent communication chains. Up until now, most AI agent interaction was limited to the AI agent and a human user. In the future, we can expect to see more agent-to-agent interactions as illustrated in the following diagram:

Security administrators will be able to create granular adaptive access policies such as conditional access policies that target both the actor (left side) independently of the resource (right side) to help ensure agent communication remains compliant with organizational security policies.

To perform its intended services, a given AI agent may call web APIs or access knowledge bases, including accessing content from the web. However, an AI agent’s ability to dynamically discover, during runtime, other AI agents in the environment that can perform specialized tasks and invoke them on-the-fly truly represents the ultimate vision of Agentic AI.

Agent Identity Blueprint as a Template for Agent Instances

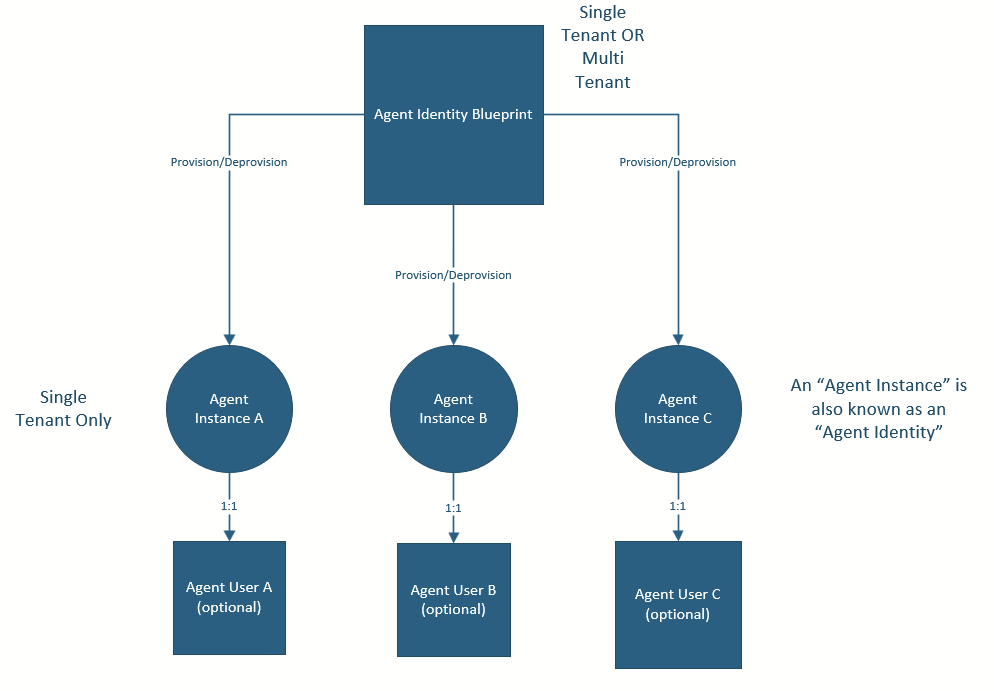

Microsoft’s vision for agentic AI in the enterprise is that AI agents are able to be treated as ephemeral/transient, which means that many agent instances may be provisioned and de-provisioned from a shared “blueprint”. To further this vision, Microsoft has introduced the following fundamental concepts and terminology as illustrated in the diagram below:

Agent instances can only be provisioned and de-provisioned by an Agent Identity Blueprint. For example, an organization can develop an internal line-of-business (LOB) agent blueprint (i.e. single-tenant blueprint) that is then used to rapidly onboard and off-board agent instances in their organizational tenant. More specifically, a single organization-wide agent identity blueprint may be created, but then each business unit or project may provision its own agent instance from that blueprint.

While some settings will be set at the agent identity blueprint level, the individual agent instances will be able to override various settings, such as specifying the name of their agent instances, modifying agent instance sponsors, and changing agent user configurations. As well, agent instances may define their own permissions and even be granted access to resources via access packages. To support multi-instance scenarios at scale, some permissions may be inherited from the agent instance’s blueprint.

Therefore, each agent instance can have its own unique name and identifier tailored to the specific context in which it is operating, such a specific business unit, geographic area, or project.

In contrast, first party agents developed by Microsoft or third party agents built by ISVs can be offered via multi-tenant agent identity blueprints, which means that once an organizational administrator grants consent, the ISV will be able to onboard and off-board agent instances into that specific organizational directory via the agent identity blueprint principal that is projected into the organizations’ directory.

This will enable ISVs to offer AI agents as services that can be consumed by various organizational departments and will most likely play a major role in enterprise-wide adoption of agentic AI.

Agent Access Patterns

An agent instance can operate in the following three modes:

- On-Behalf-Of (i.e. interactive agent)

- An agent instance accesses resources on behalf of a human. For example, an interactive agent will leverage the signed-in user’s identity to perform operations on behalf of a human user.

- Autonomous (i.e. autonomous agent)

- An agent instance will act autonomously without user context and perform app-only operations using its own identity.

- Agent User (i.e. autonomous agent with “user” context)

- An agent instance may require the ability to interact with resources on its own behalf using a user principal that will be created for itself. For example, if an agent instance needs to communicate with an API that requires a regular human user account, the agent instance will be able to leverage its corresponding agent user principal. In fact, the agent user can have a name and a photo, a mailbox for sending/receiving emails, show up in Teams notifications, join meetings, have Microsoft 365 licenses assigned to it, etc.

More simple AI agents will use the on-behalf-of flow or be autonomous in nature with no user context. In contrast, agents leveraging the agent user capability will be able to interact more seamlessly with humans and represent themselves as digital colleagues in business processes.

AI agent instances will be able to leverage tools, such as those exposed through Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers, to perform operations across Microsoft 365 productivity services, such as Outlook, SharePoint, Word, Teams, PowerPoint, Excel, and so on. In fact, a computer-using agent (CUA) will be yet another tool that will enable the AI agent to perform GUI-based operations such as browsing to a website, filling out forms, and downloading content that may not be programmatically accessible or available via a web API.

Every agent instance will need to have human oversight and supervision, so there is a concept of an agent owner to manage the technical IT administration of agents, such as its permissions, and an agent sponsor who is more of a business sponsor that may use the agent as part of a business process and can determine whether or not the agent is working as intended, approve transactions, and determine if the agent instance has reached its useful end of life. Interestingly, a sponsor of an agent instance must always be a human, while the owner may be a human or a service principal/workload identity.

Agent Identity versus Workload Identity

One of the most important concepts to understand is that while AI agents are software workload entities, they behave differently and require the resources they access to know and understand that they are being accessed by a non-deterministic software entity, rather than a traditional workload identity whose behavior is well defined and deterministic.

In Microsoft Entra Agent ID, every entity has a unique identifier, including the agent identity blueprint, agent instances that each have unique identifiers, and the agent user that also has a unique identifier. For example, in the agent user scenario, if an agent instance wants to send an email, the email service will be able to determine the specific agent instance identifier, alongside the specific agent user identifier on whose behalf the agent instance is sending the email.

Entra Agent ID considers agent instances to be OAuth 2.0 confidential clients, not public clients, and this is true across all agent access patterns. For example, in the on-behalf-of flow, a public client application (such as Microsoft Teams or a mobile app) will authenticate the human user and then send a request to the server-side agent instance. That agent instance, in turn, will then perform a token exchange, and then send requests to its dependent APIs or resources on behalf of that human user. The other two agent access patterns are simpler in the sense that there is no public client application in the flow because those AI agents don’t have a user interface (UI) component.

Importantly, in Microsoft’s AI agent design, an AI agent may or may not have a graphical user interface (GUI) component, since a GUI component won’t be needed for agent-to-agent interactions. Nonetheless, to communicate with human users for both sending notifications to them and receiving instructions from them, an autonomous AI agent will be able to leverage tools that will be available to it for such agent-to-human and human-to-agent interaction.

Agent Registry

Agent instances can be registered in an agent registry which will help with agent discoverability and communications. When an agent instance is registered in the agent registry, it will have an associated agent manifest that contains agent instance metadata with information such as agent skills, capabilities, endpoint, authentication requirements, and so forth. Client agents that need to communicate with remote agents will leverage the agent registry to discover other agents that have the necessary skills and will be able to dynamically determine the remote agents’ authentication and communication requirements.

Agents in the agent registry can be developed using different frameworks and be owned by different owners. Agent discovery will be performed on-the-fly during runtime, so client agents will be able to discover compatible agents via the agent registry and then be able to communicate directly with those agents in a point-to-point manner. However, it doesn’t take much imagination to imagine other more complex scenarios such as a publish/subscribe pattern whereby a client agent places a notification event on a queue, and, if interested, multiple remote agents will be able to pick up that notification and perform some task without ever communicating with the client agent directly.

Conclusion

Microsoft isn’t the only vendor that is rapidly developing agentic AI capabilities. Although their current focus is on agentic workforce scenarios, there are other identity and access management (IAM) vendors, such as Auth0 by Okta, that are developing agentic AI capabilities for consumers. For example, Okta is enabling end users to authenticate with agents, be able to connect agents to 3rd-party APIs that the end user has consented/approved, enable agents to perform human-in-the-loop (HITL) authorization by sending an asynchronous approval request to the end user before performing sensitive operations, and enable fine-grained authorization (FGA) for retrieval augmented generation (RAG) to ensure that large language models (LLMs) only receive the context that the end user who is using the AI agent has permissions to access, as this is especially important for AI agents that operate as knowledge-based assistants.

Agentic AI is positioned to dramatically increase the surface area for interactions that require digital identities. In Microsoft’s architecture, agent identities will be able to be placed into security groups, assigned application roles and API permissions, and Microsoft Entra roles.

Cloud computing was fundamentally an IT-led digital transformation that did not significantly change existing business processes – there was very little disruption to end users because it did not affect their user experience (UX). In contrast, however, agentic AI has the potential to dramatically change how end users interact with software and re-wire existing business processes.

In fact, if agentic AI is successful, it may bring about the largest change that end users have experienced in human-computer interaction since the introduction of the graphical user interface (GUI).

AI agents are first-class digital entities that have their own agent IDs, separate from human user accounts and traditional workload identities. The introduction of the agent user concept will further enable AI agents to operate autonomously on behalf of themselves and represent themselves as “users” in graphical user interfaces and business processes.

The ultimate vision is to have an agentic workforce, with AI agents working autonomously or semi-autonomously on behalf of individual people, on behalf of enterprise teams, or even on behalf of the organization itself in inter-organizational agentic interactions.

These are very early days for Agentic AI, both for consumers as well as enterprises, but Microsoft’s Entra Agent ID platform sheds light on the future direction and paves the path for innovation to both transform how business applications are developed (from an IT perspective), as well as to transform how business users interact with applications (from a business process perspective).

Well written and informative. Thank you!