Application access control determines what actions a user (or other non-human identity) can or cannot perform with a given resource. Authorization is a critical part of access control and can be accomplished using the following options:

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC)

- Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC), also known as Policy-Based Access Control (PBAC)

- Relationship-Based Access Control (ReBAC)

Interestingly, authorization is in many ways even more complex than authentication. While authentication determines who the entity is, authorization determines what the entity can or cannot do. RBAC is the simplest to implement, while ABAC and ReBAC are the most complex authorization models. RBAC enables coarse-grained authorization, while ABAC and ReBAC offer more fine-grained authorization capabilities. As a result, to determine which access control model to use, you will first need to determine if your application requires coarse-grained access control or fine-grained access control.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC)

RBAC is based on roles, and each role has a set of permissions. For example, a user can have an owner role, a contributor role, or a reader role, and the application will decide what the user can do based on the specific permissions that are associated with each role. RBAC roles are assigned to users and are not tied to any resource instance granularity. So, as an example, a user with a reader role can read all resources/content in an application. This is the reason that RBAC is known as coarse-grained authorization. RBAC is simple to implement and maintain.

Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC)/Policy-Based Access Control (PBAC)

ABAC, unlike RBAC, isn’t based on roles, but rather on a policy. Policies define how attributes are evaluated. Policies can leverage attributes of the user, action, resource, and environment to determine whether to grant or deny access. For example, a policy might allow users within a specific department to modify classified documents from a given location during a specific time of the day. That is, the access control decision is based on attributes of the following objects:

- User (i.e. Finance department)

- Resource (i.e. classified document)

- Action (i.e. modification)

- Environment (i.e. location or time of day)

Although ABAC/PBAC enables fine-grained access control, it’s based on policies that define the attributes to evaluate and their conditions, and so it’s more complex to implement and maintain in comparison to access control that relies on RBAC.

Relationship-Based Access Control (ReBAC)

RBAC and ABAC don’t work well for applications that support user-generated content, because in both RBAC and ABAC access control models, the access decision is not tied to a specific resource instance the user is accessing, but rather it is based on resource types. For example, RBAC and ABAC may allow a user to access all classified documents, but it’s not possible to allow access only to a specific classified document.

Similarly to ABAC, ReBAC enables fine-grained authorization, and relies on a constantly changing database (usually implemented as a graph database) that stores the relationships/connections between users, actions, and resources. In RBAC or ABAC there is no need for such a database, since access decisions can be made by simply examining the role/permissions (in the case of RBAC), or the policy (in the case of ABAC). For example, in ReBAC, access can be granted to a user to perform an action on a specific resource, such as to view a given document (and no other document). ReBAC can model complex relationships between various objects (i.e. such as users and their resources), and the database will need to be queried to determine whether to grant or deny access during an access decision.

Interestingly, unlike ABAC which is policy-based, ReBAC is graph-based, and the graph-based nature of the database that is used in ReBAC can introduce the ability to have more complex relationship hierarchies that are not only modeled as direct relationships, but it can also infer indirect relationships. For example, if User A has an owner relationship to Folder B, and this relationship is explicit in the graph database, and that same user attempts to read/write File C within that Folder B, access may be granted, even though there isn’t a direct relationship between User A and File C. Such indirect relationships cannot be modeled using RBAC or ABAC.

Conclusion

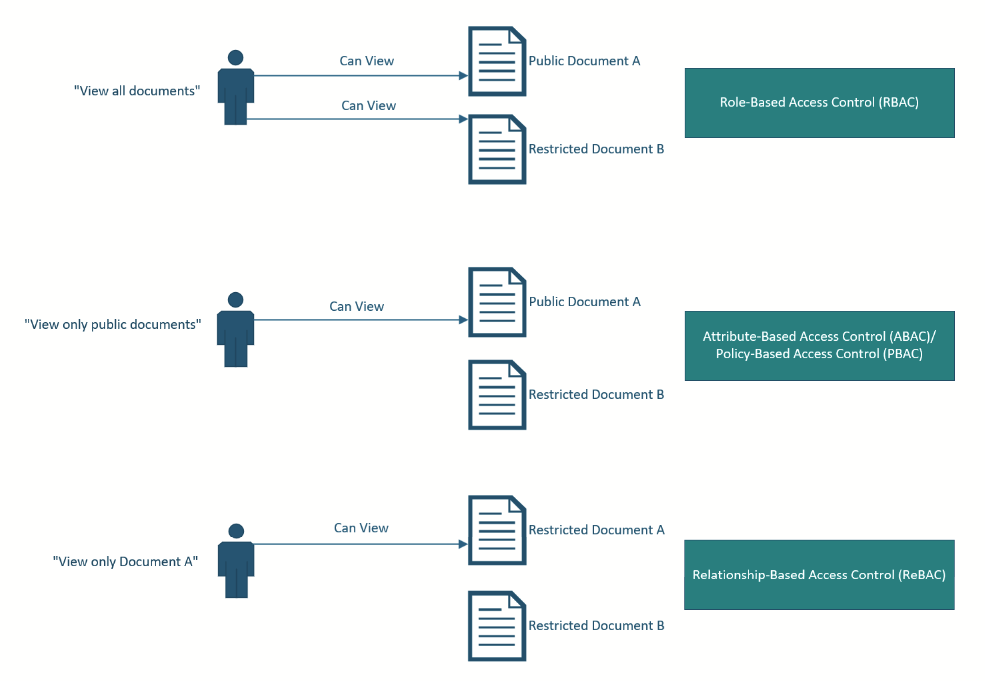

There is no silver bullet access control strategy because the business requirements for each application are different. The goal is to choose the simplest access control method considering both implementation and maintenance complexity. The following diagram shows the fundamental difference between the three access control paradigms described above:

Some applications may work well with RBAC, while others may require ABAC or ReBAC. It’s critical to choose the most appropriate access control approach for your application, since not all applications may necessarily have the same requirements.

Importantly, choosing an access control model is mainly needed for custom-developed applications, since SaaS and COTS applications have their own access control method which you don’t generally control. When developing a custom application, consider whether it needs fine-grained authorization or coarse-grained authorization. For example, if you choose RBAC incorrectly, you may encounter a proliferation of roles if you attempt to use RBAC as a mechanism to perform fine-grained authorization. In such cases, it’s critical to choose ABAC or ReBAC from the beginning.

Finally, keep in mind that these access control paradigms are not mutually exclusive. It’s certainly possible to use them in combination. For example, many modern SaaS applications that support user-generated content enable the assignment of users to roles on specific resources, with the ability to even create custom roles. As a result, the application leverages both RBAC and ReBAC access control concepts. Furthermore, many applications rely on identity providers (IdPs) which contain adaptive access policies that determine risk based on location or other anomalous access patterns, and as such, the identity provider performs policy-based access control (PBAC). Therefore, the final decision to grant or deny access may be based on all three access control paradigms.

RBAC, ABAC, and ReBAC have their own strengths, and the decision as to which one to use should be primarily based on the implementation and maintenance complexity. The goal should be to choose the most elegant and simple access control paradigm for your application, taking into consideration any current and future business requirements for coarse-grained or fine-grained authorization, and the need or lack thereof to perform access control on user-generated content.